Genus Culcitulisphaera Riedman and Porter, 2016

Type species.—Culcitulisphaera revelata, by monotypy.

Diagnosis.—As for type species.

Etymology.—From the Latin culcitula, meaning small pillow, and sphaera; thus, a sphere covered by small pillows

Remarks.—This genus is characterized by the presence of the pillow elements of the vesicle exterior, visible in transmitted light microscopy but best understood in scanning electron microscopy

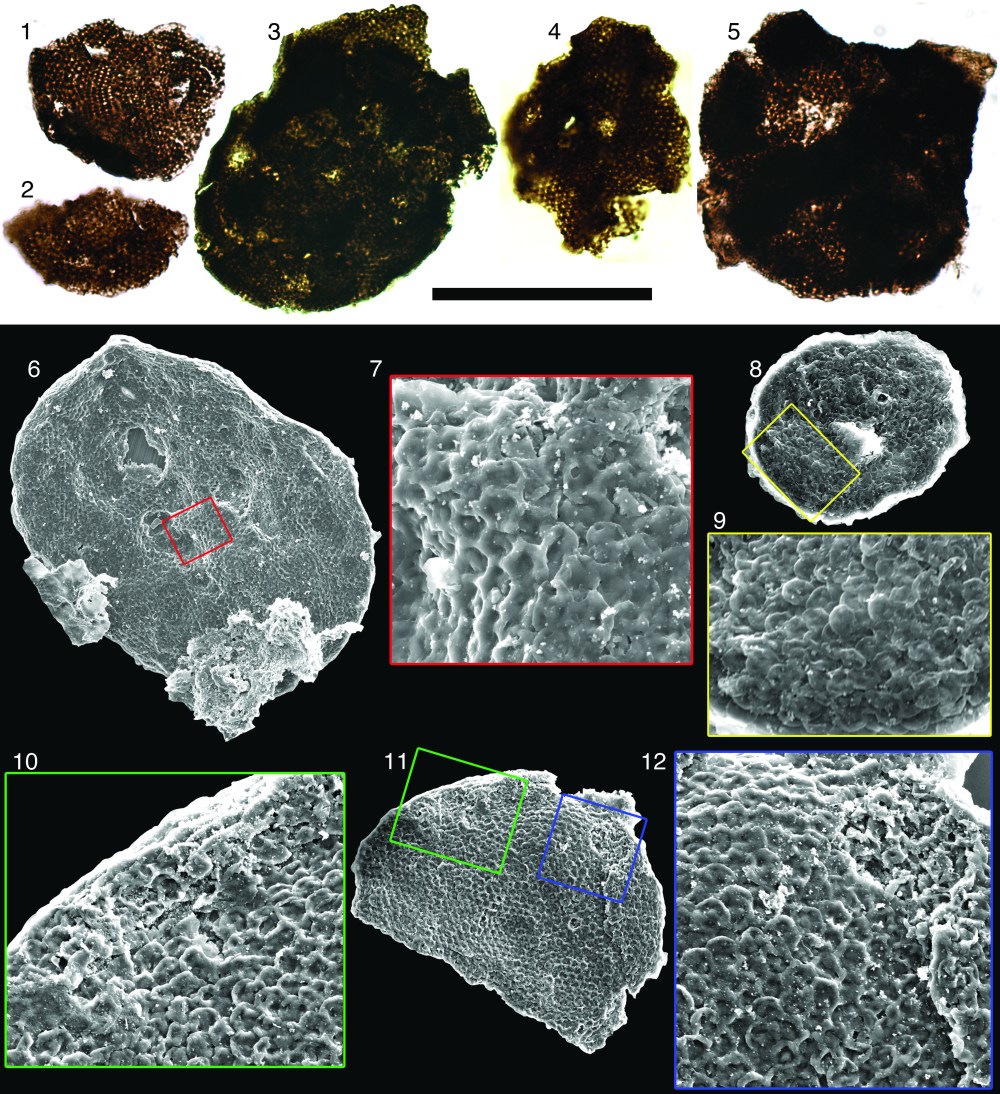

From Riedman and Porter, 2016. Culcitulisphaera revelata. (1-5) transmitted light images (6-12) scanning electron micrographs, (1) Holotype. Scale bar is 50 µm for (1–6, 8, 11) and 16 µm for (9, 10, 12).

Culcitulisphaera revelata Riedman and Porter, 2016

Non 1966 Trachyhystrichosphaera laminaritum Timofeev, p. 36, pl. 7, fig.3.

1979 Kildinella sp.; Vidal, pl. 4, figs. C, D.

?1985 Trachysphaeridium sp. A; Vidal and Ford, p. 377, figs. 8B, 8D.

1992 Trachysphaeridium laminaritum; Schopf, pl. 14, fig. A.

2009 Trachysphaeridium laminaritum; Nagy, Porter, Dehler and Shen fig. 1H.

2016 Culcitulisphaera revelata; Porter and Riedman, p. 822; figs. 5.1–5.8.

2016 Culcitulisphaera revelata; Riedman and Porter, p. 861; figs. 5, 6.4–6.6, 7, 8.

Holoype.— (Fig. 5.1), SAM Collection number P49519, Slide 1265.57-19A, coordinate N24-1, depth of 1265.56 m, Giles-1 drillcore, Alinya Formation.

Diagnosis.—Optically dense sphaeromorphic organic-walled microfossil distinguished by a surface ornament of tightly packed 1 to 3 µm cushion-shaped outpockets of the vesicle that may appear only as ~1 µm diameter light spots or alveolae under transmitted light microscopy.

Occurrence.—Appears in late Mesoproterozoic to middle Neoproterozoic units: the uppermost Limestone Dolomite “series” (beds 19-20) of the Eleonore Bay Group of East Greenland (Vidal, 1979), the Chuar Group of southwestern United States (Nagy et al., 2009; Porter and Riedman, 2016), Alinya Formation of Office Basin, Australia (Riedman and Porter, 2016) and the Lakhanda Group of Siberia (Schopf, 1992, however, see below).

Description.—Optically dense organic vesicle circular to ellipsoidal in outline, ranging in diameter from 34.6 to 88.4 µm, reflecting an originally sphaerical to sub-sphaerical shape. Vesicle surface consists of small circular to sub-circular outpockets. The outpocket elements range in diameter from 1.3 to 2.7µm. Vesicular elements are unlikely to have been surficial scales as none has yet been found separated from the vesicle surface and inspection of all specimens suggests full attachment to the vesicle. Thus far these vesicular elements have been recognized only under SEM. When specimens are viewed with transmitted light microscopy the surface appears to have small (~0.7µm) alveolae or hemisphaerical depressions in the vesicle, which are in fact the centers of the outpockets where light passes through fewer layers of vesicle. Occasionally these structures can be recognized as cushion-shaped elements along the periphery of a specimen as viewed under light microscopy (Fig. 1.1–1.5).

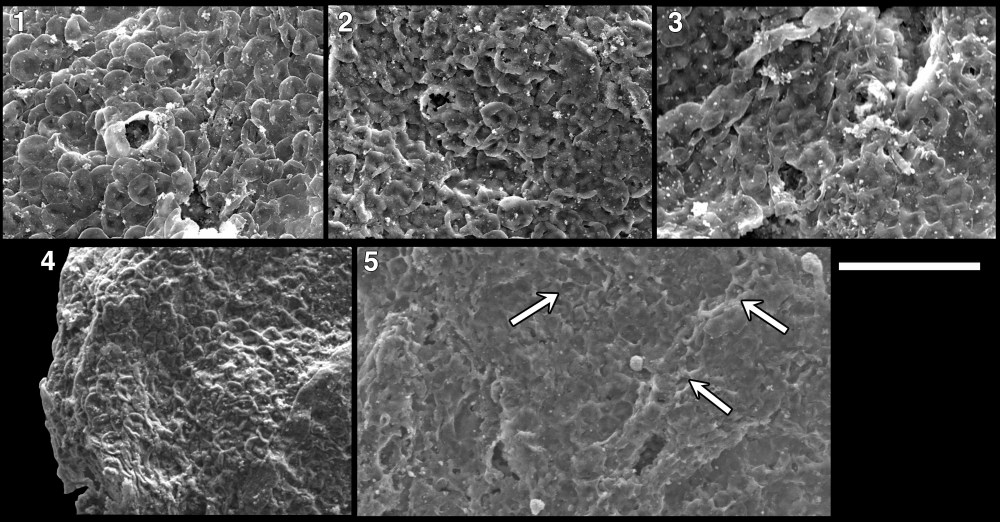

A spectrum of taphonomic variation is seen in C. revelata specimens. Study of these variants has been informative for developing an understanding of the vesicle morphology (for example, by providing evidence of the hollow nature of the pillow-shaped elements and indication that the wall is composed of individual pillow-elements rather than bearing only a textured surface). The flexibility of the vesicle wall is indicated in the folding that occurs in the elements along the perimeter of the flattened fossil, giving an imbricated appearance (Fig. 2.4). During degradation the pillow elements of the vesicle appear to “deflate”; the outer wall of the element sinks into the underlying cavity (Fig. 1.7, 1.12, 2.3), creating a honeycomb-like appearance. Occasionally the outermost skin of the pillows shows rupture (Figs. 2.1 and 2.2) or appears to have been sheared away from the fossil (arrows in Fig. 2.5), revealing a smooth surface within. Several of the fossils studied here also show a wart-like crater that excavates through the vesicle layers (Figs. 1.6, 1.11, 1.12); this feature is not interpreted as an excystment structure, but more likely represents taphonomic processes.

From Riedman and Porter, 2016. Culcitulisphaera revelata in sequence of taphonomic degradation. Pillow-like elements become progressively sunken and in some instances the tops of the pillow is sheared away (white arrows). Scale bar 10 µm.

Etymology.—From the Latin revelatum, meaning “revealed”, referring to the fact that the pillow elements of the vesicle were unknown until revealed by SEM.

Remarks.—C. revelata is not considered to be conspecific or congeneric with Trachysphaeridium laminaritum, although this was thought a likely taxonomic home for these specimens due to similarities with specimens figured by Schopf et al. (1992) and Nagy et al. (2009). The original diagnosis and description of T. laminaritum (Timofeev, 1966) are vague and do not mention features considered diagnostic of C. revelata (i.e. alveolae or circular to cushion shaped vesicular elements), instead describing a thick-walled vesicle with a chagrinate texture ranging from 70 to 250 mm in diameter (typically 120 to 200mm)– larger than the 35 to 88mm diameter specimens recovered from the Alinya Formation. Additionally, the fossil images of T. laminaritum (plate 7, figure 3; hand drawn illustrations) do not conclusively illustrate diagnostic features of this taxon.

The fossil imaged in plate 14, figure A, p. 1075 of Schopf et al. (1992) appears to be C. revelata. The caption reads, “Trachysphaeridium laminaritum Timofeev in press HOLOTYPE” and the fossil is indicated as being from the Lakhanda Group of Siberia (the publication “in press” is unclear and not listed in the bibliography). The “holotype” designation in the caption is apparently incorrect as the holotype Timofeev (1966) designated for T. laminaritum was from a drill core taken from northern Moldova, not from the Lakhanda Group of Siberia. Differences in diameter and outline indicate these are two distinct specimens. There would have been no need to have designated a neotype in 1992 as Timofeev’s original specimens were still available for study as of 1996 (Knoll, 1996; contra Jankauskas et al., 1989). In any case, the specimen figured by Schopf (1992) indicates that C. revelata was a part of the ca. 1 Ga Lakhanda biota, extending this form’s geographic and stratigraphic range.

References:

Jankauskas, T.V., Mikhailova, N.S. and Hermann (German), T.N. eds., 1989, Mikrofossilii Dokembriia SSSR (Precambrian microfossils of the USSR). Nauka, Leningrad. 191 p.

Knoll, A.H., 1996, Archean and Proterozoic paleontology, in Jansonius, J. and McGregor, D.C. eds., Palynology: principles and applications. American Association of Stratigraphic Palynologists Foundation, v. 1, p. 51–80.

Schopf, J.W., 1992, Atlas of representative Proterozoic microfossils, in Schopf, J.W. ed., The Proterozoic Biosphere. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, p. 1055–1117.

Timofeev, B.V., 1966, Mikropaleofitologicheskoe Issledovanie Drevnikh Svit (Micropaleophytological study of Ancient Suite). Nauka, Moscow, 147 p., 89 plates. (in Russian).

Vidal, G., 1979, Acritarchs form the upper Proterozoic and lower Cambrian of East Greenland: Grønlands Geologiske Undersøgelse, Bulletin 134, 40 p., 7 pl.

Vidal, G. and Ford, T.D., 1985, Microbiotas from the Late Proterozoic Chuar Group (Northern Arizona) and Uinta Mountain Group (Utah) and their chronostratigraphic implications: Precambrian Research, v. 28, p. 349–389.