Figure 1. Geologic Time Scale

The Precambrian Eon (Figure 1: Geologic Time scale) is, by definition, all of time before the start of the Cambrian Period ~541 million years ago. The formation of the Earth occurred ~4.5 billion years ago and the oldest evidence of life is ~3.5 billion years old in layered structures from Australia (Figure 2: Stromatolites and ?Stromatolites) thought to have been deposited by a combination of biological and physical processes (Hofmann et al., 1999) as well as organic residues that are considered likely to have a biologic origin (Hickman-Lewis et al., 2016). That said, there are somewhat similar structures (Figure 2: Stromatolites and ?Stromatolites) recently reported from 3.7 billion year old rocks form Greenland that hint at a biological influence (Nutman et al., 2016).

Figure 2. Stromatolites of ~3.5 billion year old Warrawoona Group, Australia

Thus it appears that life had not only appeared within 1 billion years of Earth’s formation, but had become abundant and sophisticated enough to create large, multi-layered structures by that time. These early cells were likely similar- if not identical to- some modern bacteria in the way they made their energy and in the fact that they lacked the nuclei and organelles that distinguish eukaryotes (Figure 3: Prokaryotes and Eukaryotes).

Figure 3. Prokaryotic and Eukaryotic cells from Wikipedia

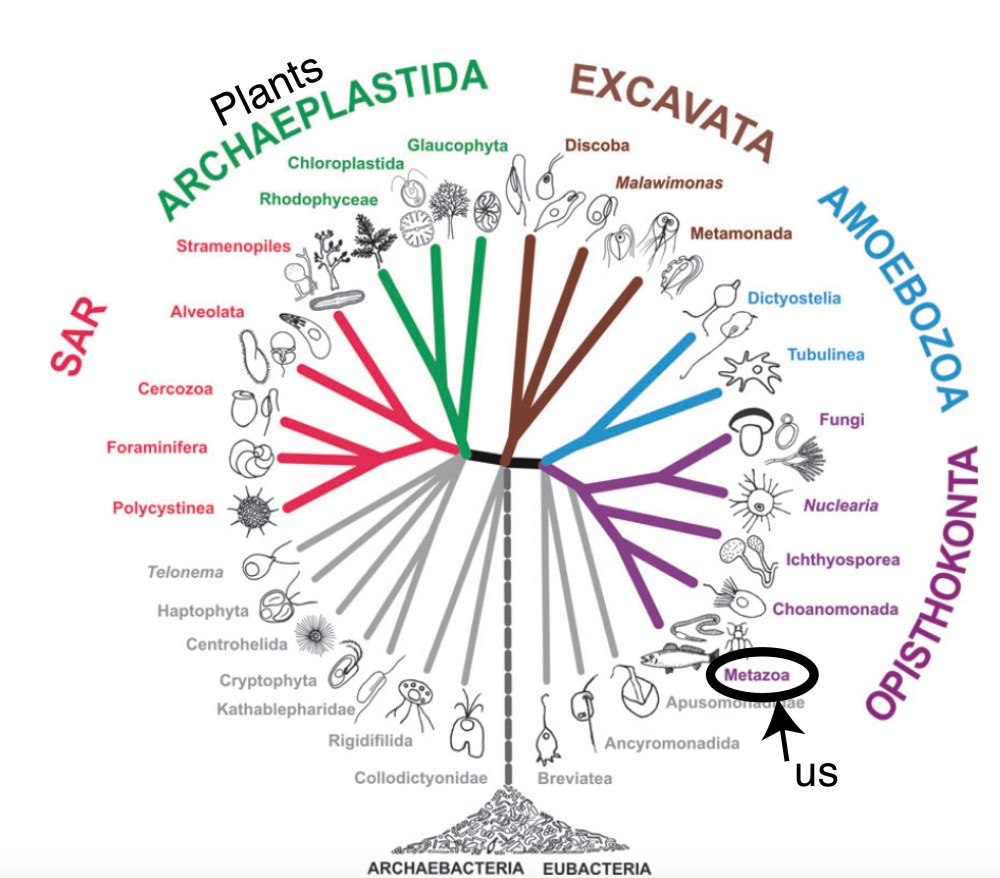

Bacteria and the less well-known, but fantastically interesting Archaea (see here too) (together known as the prokaryotes) account for tremendous diversity in the modern world— but a diversity in their metabolic approaches to making a living rather than the diversity of physical forms seen in the relatively metabolically boring eukaryotes. My admiration for prokaryotes not withstanding, my research and this website focuses (for now) on the Precambrian history of eukaryotes. Aaaand amazingly, I can be even more specific!— my research focuses on single-celled eukaryotes of the Precambrian! Single celled forms are found in all of the modern eukaryotic groups (Figure 4: Tree of Eukaryotic Life), so the grouping (known as protists) is not a real biological group, just one based on the shared character of being composed of only one cell.

Figure 4 Eukaryotic tree modified from Adl et al., 2012.

Because neither genetic information nor the distinctive nuclei and organelles of eukaryotes are preserved during fossilization, it can be maddeningly difficult to distinguish between prokaryotic and eukaryotic fossils. Eukaryote cells are often, but not always larger than prokaryotic cells, which typically top out around 60 micrometers (mm) in diameter (about the diameter of a human hair; Figure 5: How big is a micron?).

Figure 5 How big is a micron? From socalwatertreatment.com

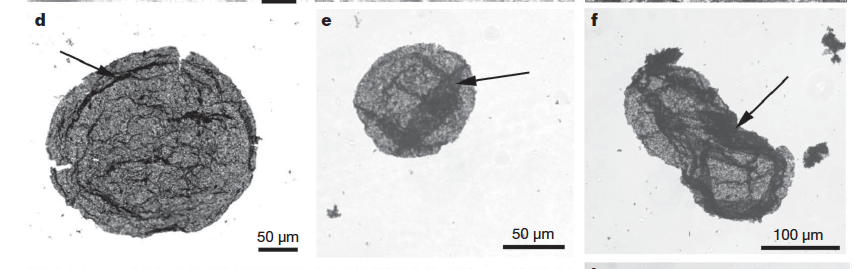

Possible early eukaryote body fossils (Figure 6: Really old ?eukaryotes?) have been reported from South African rocks as old at 3.2 billion years old (Javaux et al., 2010). These fossils appear to have originally been sphaeroidal, their organic walls having been flattened by deep burial. They range in diameter from 31 to ~300 mm—ranging from sizes well within those expected of bacteria to those considered highly unusual for bacteria but typical of eukaryotes. Unfortunately, there are few of these fossils and they have no indisputable characters to distinguish them as eukaryotes, much less anything more specific.

Figure 6 Organic-walled microfossils from 3.2 billion year old, Moodies Group South Africa- Javaux et al, 2010.

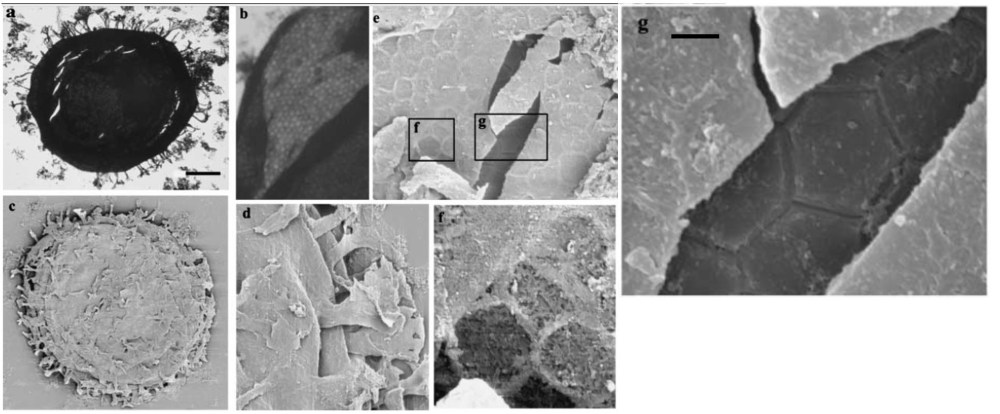

Much more complex fossils have been recovered from ~1.6 billion year old rocks from northern China and ~1.5 billion year old Australian rocks (Yin et al., 1997; Javaux et al., 2004) Some of the fossils (Figure 7: Tappania plana) are not especially large (30 to 60 mm in diameter) but do have tubular extensions from their surfaces called processes as well as large extended openings on the cell. Because of the large, extended ‘necks’ and irregular nature of these processes—characters not seen in prokaryotes— these fossils, known as Tappania plana, are considered to be definite eukaryotes. From some of the Chinese rocks comes a beautifully complex fossil (with a name to match: Shuiyousphaeridium macroreticulatum). This fossil also has tubular processes, but with flaring ends. The surface of S. macroreticulatum is especially interesting, though— it is composed of closely packed polygonal plates with tapered edges (Figure 8: Shuiyousphaeridium macroreticulatum). Again, these are complex structures never seen in prokaryotes, thus these must be fossils of eukaryotes– but what kind? (we’re still working on that one.)

Figure 7. Tappania plana from (1.5 to 1.4 billion year old) Roper Group, Australia- Javaux et al 2004; and from ~1.6 billion year old Ruyang Group, China- Yin, L-M., et al., 2005 Scale bar in A is 35 mm for A, 20mm for B, 25 mm for C. Scale bar in 9 is 16mm for (1), 23mm for (2), 26mm for (3), 27 mm for (4), 22 mm for (5), 17 mm for (6), 24 mm for (7), 4.2 mm for (9 and 10).

Figure 8 Shuiyousphaeridium macroreticulatum from 1.6 billion year old Ruyang Group, China- Javaux et al., 2004. Scale bar is 50 mm for A and C, 13 mm for B, 10 mm for D, 2.5 mm for E and 1mm for F and G

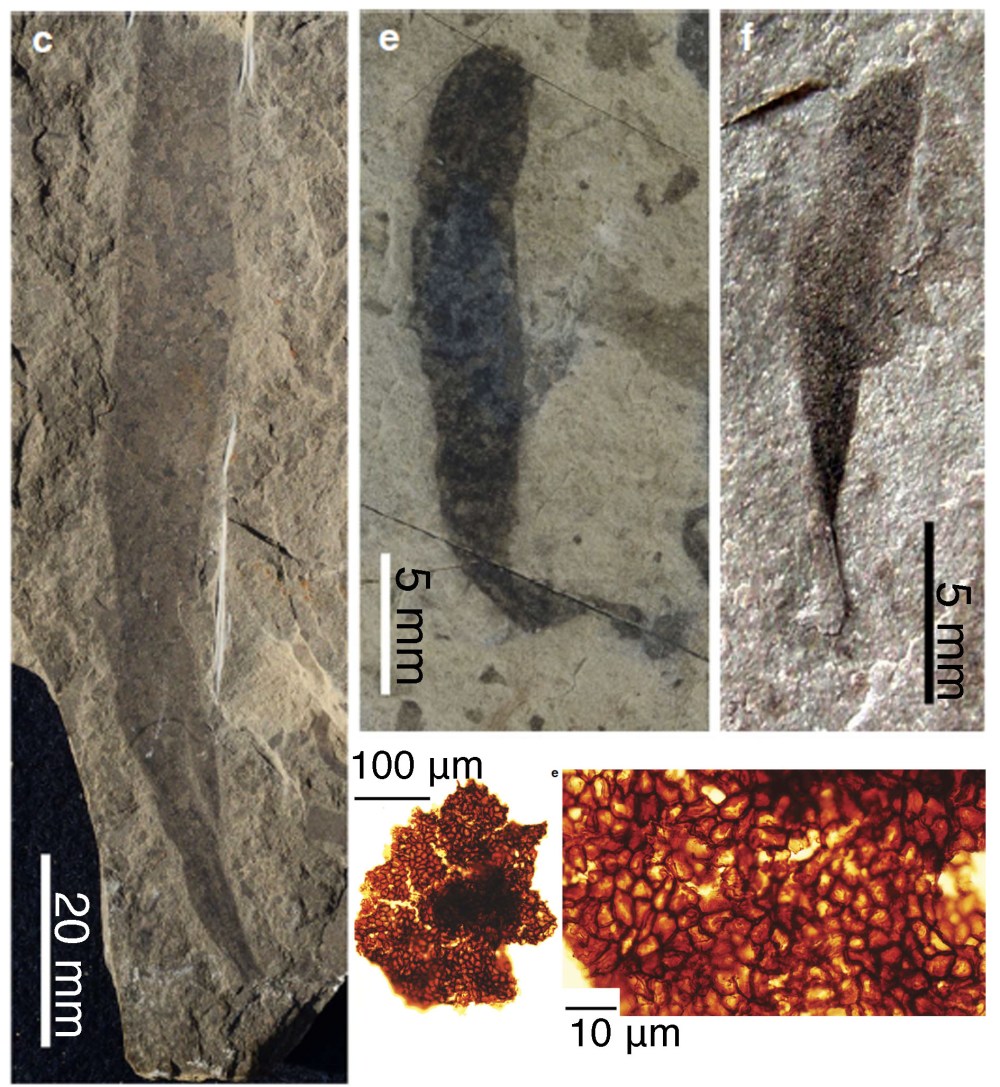

In other rocks from northern China (~ 1.56 billion years old) there have very recently been reported some quite large fossils—nearly a foot long (Figure 9, Zhu et al 2016)! These are very thin and flat blade-like fossils that quite likely were attached to the sea floor and photosynthetic, living in a mode seen in many modern seaweeds. From the same rocks were found fragments of multicelled sheets (Figure 9: blade-like macrofossils and multi celled sheets); although the large ribbon-like specimens don’t preserve the fine enough detail to see if they were multicellular, their large size and close association with the millimeter-scale multicelled fragments strongly suggests they were.

Figure 9 blade-like macrofossils and multicelled sheets from Gaoyuzhuang Formation, North China- Zhu et al., 2016.

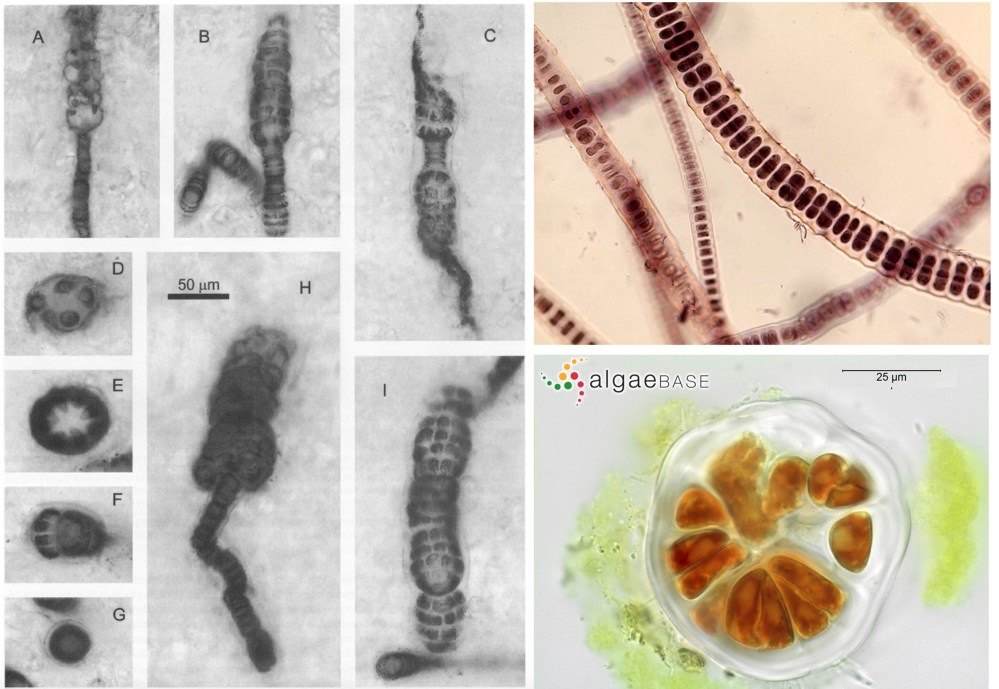

One of the few Precambrian fossils that has been placed not only in the eukaryotes but within one of the large modern eukaryotic groups is Bangiomorpha pubecens (Figure 10: Bangiomorpha pubecens and modern Bangia sp.), a lovely and complex filamentous fossil from about 1.2 billion year old rocks of Canada. This fossil’s cellular differentiation not only indicates its place within the red algae, similar to some modern forms (Figure 10), but is also significant in itself as some of the first evidence of specialized structures in multicellular organisms.

Figure 10 Bangiomorpha pubecens from the ~1.2 billion year or Hunting Formation, Canada- Butterfield, 2000. Scale bar in H is 50 mm for all. And modern Bangia sp. from http://cfb.unh.edu/phycokey/phycokey.htm (top right) and http://www.algaebase.org (bottom right)

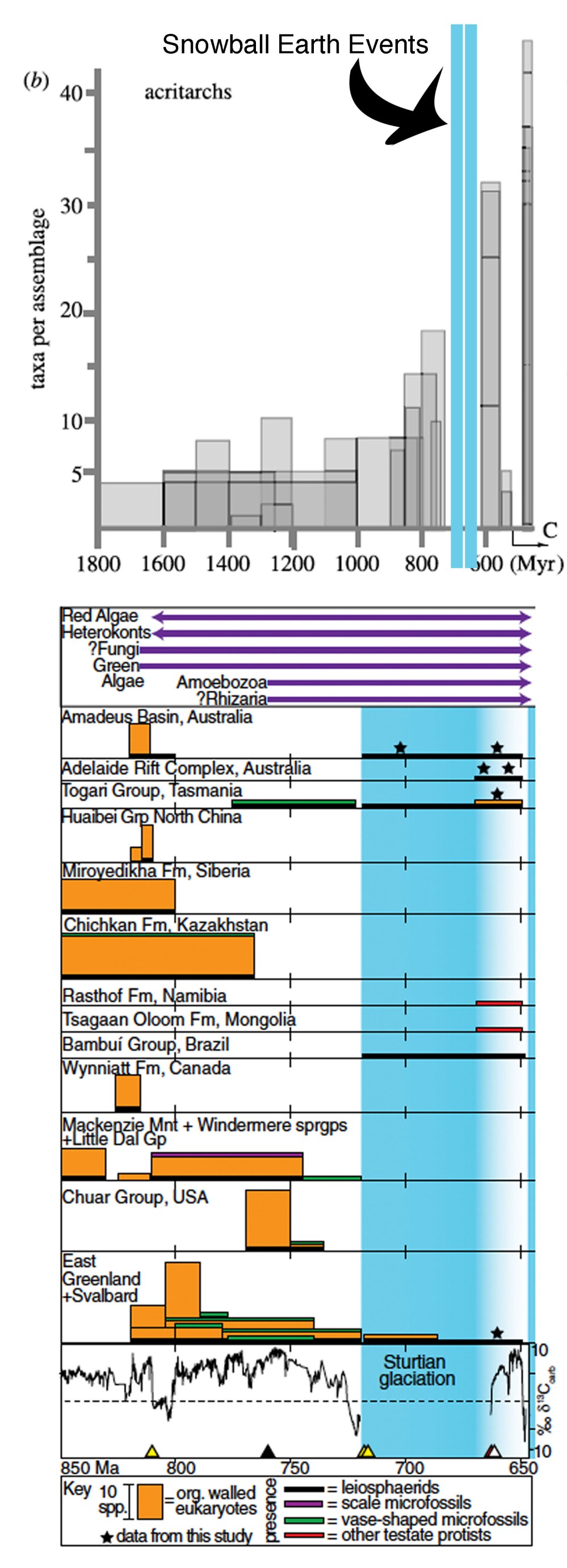

As time marched forward the diversity of eukaryotes increased (Figure 11: Eukaryotic Diversity of the Proterozoic). Although we still can’t say much about exactly which groups of eukaryotes these were (e.g. red or green algae, fungi, animals?) we can see that the variety of forms increased— until around ~740 million years ago. It appears that Earth’s first extinction event might have occurred around this time— many old friends, species that had been around for nearly a billion years disappeared, a totally new group, the vase-shaped microfossils appeared briefly and disappeared, and then eukaryote diversity flat-lined for more than 100 million years (Knoll et al., 2006; Riedman et al., 2014, Cohen and Macdonald, 2015). The reason for this loss of diversity is not yet clear; it had been tentatively associated with the global glaciations known as Snowball Earth— at least twice in the late Precambrian Earth is thought to have pretty much frozen over with glaciers forming at sea level, at the equator. However, ages of both the fossil-bearing rocks and the glacially influenced rocks have been refined over the decades and now indicate about a 20 million year gap between them; the first of the Snowball Earth glaciations seems to have started around 720 million years ago. It is certainly possible- likely in fact- that the extinctions were caused by environmental shifts that preceded and maybe led to the glaciations, but with a ~20 million year time gap, the extinctions couldn’t have been caused by glacial cold.

Figure 11 Diversity of single-celled eukaryotes (top) 1800 to 600 million years ago- modified from Knoll et al., 2006, and (bottom) 850 million years ago to 650 million years ago- Riedman et al., 2014.

Eukaryotic diversity rebounded with new species sometime after the end of the second glaciation ~635 million years ago. During the latest Precambrian, the Ediacaran Period— new, highly ornamented single-celled fossils abound and macrofossils (visible by naked eye) become abundant. From here (and here) eukaryotes are really off to the races.

Cited References:

Adl, S. M. et al., 2012. The revised classification of eukaryotes. The Journal of Eukaryotic Microbiology. V. 59, 429-493. DOI: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.2012.00644.x

Butterfield, N. J., Bangiomorpha pubecens n. gen, n. sp., Implications for the evolution of sex, multicellularity and the Mesoproterozoic/Neoproterozoic radiation of eukaryotes. Paleobiology, v. 26, p. 386–404.

Cohen, P. A. and Macdonald, F. A., 2015. The Proterozoic record of eukaryotes. Paleobiology, v. 41, p. 610–632. DOI: 10.1017/pab.2015.25

Hickman-Lewis, K., Garwood, R. J., Brasier, M. D., Goral, T., Jiang, H., McLoughlin, N., Wacey, D. 2016. Carbonaceous microstructures from sedimentary laminated chert within the 3.46 Ga Apex Basalt, Chinaman Creek Locality, Pilbara, Western Australia, v. 278, p161–178. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.precamres.2016.03.013

Hofmann, H. J., Grey, K., Hickman A. H., Thorpe, R. I. 1999. Origin of 3.45 Ga coniform stromatolites in Warrawoona Group, Western Australia. Geological Society of America Bulletin, v.111, p. 1256–1262. doi:10.1130/0016-7606(1999)111<1256:OOGCSI>2.3.CO;2

Javaux, E., Knoll, A. H., Walter, M. R., 2004. TEM evidence for eukaryotic diversity in mid-Proterozoic oceans. Geobiology, v. 2, p. 121–132.

Javaux, E. J., Marshall, C. P., Bekker, A., 2010. Organic-walled microfossils in 3.2 billion-year old shallow marine siliciclastic deposits. Nature, v. 463, p. 934–938. doi:10.1038/nature08793

Knoll, A. H., Javaux, E. J., Hewitt, D., Cohen, P., Eukaryotic organisms in Proterozoic oceans. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society, B. v. 361, p. 1023–1038. doi:10.1098/rstb.2006.1843

Nutman, A. P., Bennett, V. C., Friend, C. R. L., Van Kranendonk, M. J., Chivas, A. R. Rapid emergence of life shown by discovery of 3,700-million-year-old microbial structures. Nature, v.537, p535–538. doi:10.1038/nature19355

Riedman, L. A., Porter, S. M., Halverson, G. P., Hurtgen, M. T., Junium, C. K., 2014. Organic-walled microfossil assemblages form glacial and interglacial Neoproterozoic units of Australia and Svalbard. Geology, v. 42, p. 1011–1014. doi:10.1130/G35901.1

Yin, L. M., 1997. Acanthomorphic acritarchs from Meso-Neoproterozoic shales of the Ruyang Group, Shanxi, China. Review of Palaeobotany and Palynology, v. 98, p15–25.

Yin, L-M, Yuan, X., Meng, F., Hu, J., 2005, Protists of the Upper Mesoproterozoic Ruyang Group in Shanxi Province, China. Precambrian Research, v. 141, p. 49–66.

Zhu, S., Zhu, M., Knoll, A. H., Yin, Z., Zhao, F., Sun. S., Qu, Y., Shi, M., Liu, H. 2016, Decimetre-scale multicellular eukaryotes form the 1.56-billion year old Gaoyuzhuang Formation in North China. Nature Communications, DOI: 10.1038/ncomms11500

Additional reading:

Butterfield, 2015. Early evolution of the Eukaryota. Palaeontology, v. 58, p5–17. doi: 10.1111/pala.12139

Knoll, 2014. Paleobiological perspectives on early eukaryotic evolution. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a016121